Alright. Let’s talk more “old-school” rules. Last week we discussed the concept of THAC0 – what it was, where it originated, and how it worked. This week we’re going to take a brief step to the left and look at something… well, not exactly related, but it does directly impact THAC0, at least partially. That’s right – we’re talking proficiencies.

Now, it’s important to note that when you’re talking about proficiencies in AD&D, there are two things that you could be referring to. The first is “weapon proficiencies” which are required tournament level but “optional for your home table” rules. The second thing that could be being referenced is the completely optional system of “non-weapon proficiencies” which were a proto-skill system for the game. And don’t you fret – we’ll be touching on each of them in this article (because I have OPINIONS on the second one).

Unlike the most recent edition of the game where every character gets a “proficiency bonus” that increases as they advance in level and is added to the d20 when making an attack with a weapon or when making a skill check that you’re proficient in, these proficiencies worked very differently back in the day.

Let’s start with weapons; your class gave you the ability to use certain types of weapons – warriors, for example, could use any weapon, while mages could only use daggers, staves, darts, knives, and slings. If it was on your approved list, you could use it without penalty.

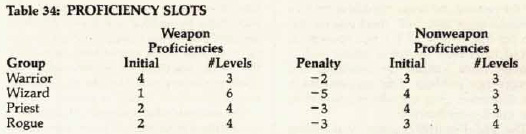

Now, if you decide to use the optional weapon proficiency system, things change somewhat. Instead, you receive a number of “proficiency slots” at first level allowing you to select a number of weapons on your class list to become “proficient” in. As you advanced in level, you gained more proficiency slots that you could spend to become proficient in more weapons. The more martial classes started with more slots, and got them more frequently.

If you were forced into a situation where you had to use a weapon that you were unfamiliar with, you would take a non-proficiency penalty to the attack roll. For a martial class like a fighter or a paladin, that penalty was only a -2. But for a mage, that penalty was a steep -5. This non-proficiency penalty was reduced by half if the weapon was related in some way to a weapon that you were proficient in – for example if you were trained to fight with a long sword but were forced into a situation where you had to fight with a bastard sword. The idea here is that the usage of the weapon is similar enough where, even if it feels somewhat awkward in your hands, it’s not completely alien. Later releases to the game eventually saw the introduction of “weapon proficiency groups” which instead gave you proficiency in multiple related weapons, essentially replacing this idea by allowing a character to become proficient in all “heavy bladed weapons” with one proficiency instead.

Furthermore, a fighter (and only a fighter) could devote a second proficiency slot to a weapon (and only one weapon) to become “specialized” with the use of that weapon, getting a bonus to both attack and damage rolls, as well as increasing the amount of attacks they get in a round (we’ll discuss how AD&D handled this in a different article). Furthermore, if specialized in a bow or crossbow, they gained the ability to fire it from “point blank range” and could give them a free missile attack at the beginning of a combat round if certain conditions were met (again, we’ll talk about missile combat and the flow of a combat round in another article).

Purists will argue that weapon proficiencies didn’t actually diversify weapon selection like they purported, but instead simply drove players to take proficiency in weapons that appeared most commonly on a magical weapon table, ultimately leading everyone to pick the same proficiencies. This argument doesn’t hold a lot of weight with me. Yes, playing without them lets a fighter pick up any weapon they can find and be effective with it, but if the magic weapons are all longswords and longbows anyway, that’s what they’re going to end up wielding regardless of whether or not you’re using weapon proficiency rules. As I’ve discussed multiple times before, this problem is endemic to every edition of Dungeons and Dragons in one capacity or another and the solution isn’t to not use weapon proficiency. Instead, it’s to include new and unique magic weapons to reward players for taking unique and uncommon weapon options when they create their character, or encourage them to diversify with a later proficiency slot by giving them an uncommon magical weapon that none of them can use early on in the campaign.

So that’s weapon proficiencies in a nutshell. Now let’s talk about non-weapon proficiencies. As I stated above, this was a proto-skill point system that allowed players to further develop their characters by letting them be good at certain non-combat things like blacksmithing or cooking or dancing or cobbling (yes, really). Just like weapon proficiencies, you got a number of “proficiency slots” at character creation to pick a number of skills for your character and you earned more as you advanced in level. Certain “more intensive” proficiencies cost more than one slot to take, and some of them were restricted to certain classes. Having this proficiency meant that you could succeed on most tasks related to that skill without a chance of failure – for example, a skilled blacksmith could easily forge horseshoes or other basic crafts of the trade without a chance of screwing it up. But what about specialized tasks within that field? Or something where failure carried the possibility of something interesting happening? Well, each of these non-weapon proficiencies was tied to a certain ability score (Strength, Intelligence, etc.) and some of them had a bonus or a penalty associated with it (Strength +1, Intelligence -2, etc.). If you ever had to make a roll in these situations, you added or subtracted the bonus or penalty from the relevant ability and picked up a d20, attempting to roll beneath the adjusted ability score. If you did, you succeeded. In these cases, a 20 was always an automatic failure.

Furthermore, you could take the same non-weapon proficiency multiple times in order to get an additional +1 bonus to those proficiency checks. On the surface, it’s a very simple system that emulates a basic skill system. But… there are some serious issues with it.

The first is the fact that it introduces a new way to resolve a check – and unlike attack rolls and saving throws where rolling high was better, this ran counter to that by demanding that you roll lower than your associated ability. Second – it places a lot of power on ability scores instead of actual training. A character with a Dexterity score of 18 or 19 was always going to be better at dancing than someone with a 12 that had sunk several non-weapon proficiencies into getting further bonuses. And finally, the shear breadth of these non-weapon proficiencies made them incredibly hard to balance – some were simply better choices than others or had more dynamic impacts on a game. And then you add in that other releases added multiple new non-weapon proficiencies or rewrote existing proficiencies from other sources and it quickly became a bloated and unbalanced mess.

It was a valiant attempt, but at the end of the day, I’ll take the current skill list every day of the week without even thinking twice about it. Heck, I’d take the cumbersome skill point system of 3rd Edition over it.

So there you have a brief overview of the proficiency systems of yore. One was all right, if not always accurately represented in the CRPGs that came out like Baldur’s Gate. The other one – not so great and unnecessarily bloated the game. Someone has gone through all of the work of compiling all of the non-weapon proficiencies released over the life of AD&D – the PDF clocks in at nearly 300 pages. It was revolutionary at the time because it simply didn’t exist in games like Dungeons and Dragons but like a lot of things from that time, it ended up being a bit much.